AN INFINITE HISTORY

AN INFINITE HISTORY

AN INFINITE HISTORY

AN INFINITE HISTORY

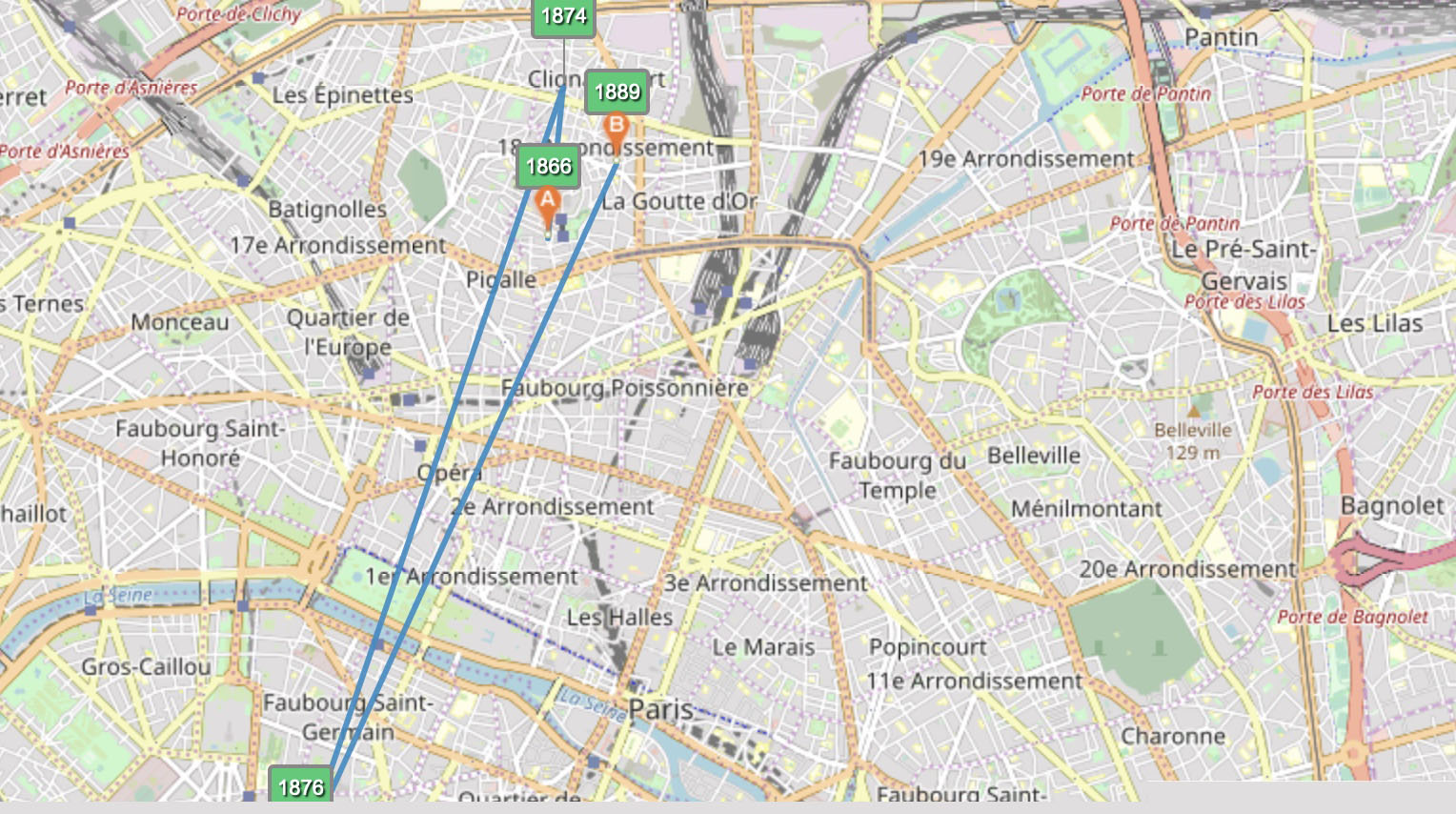

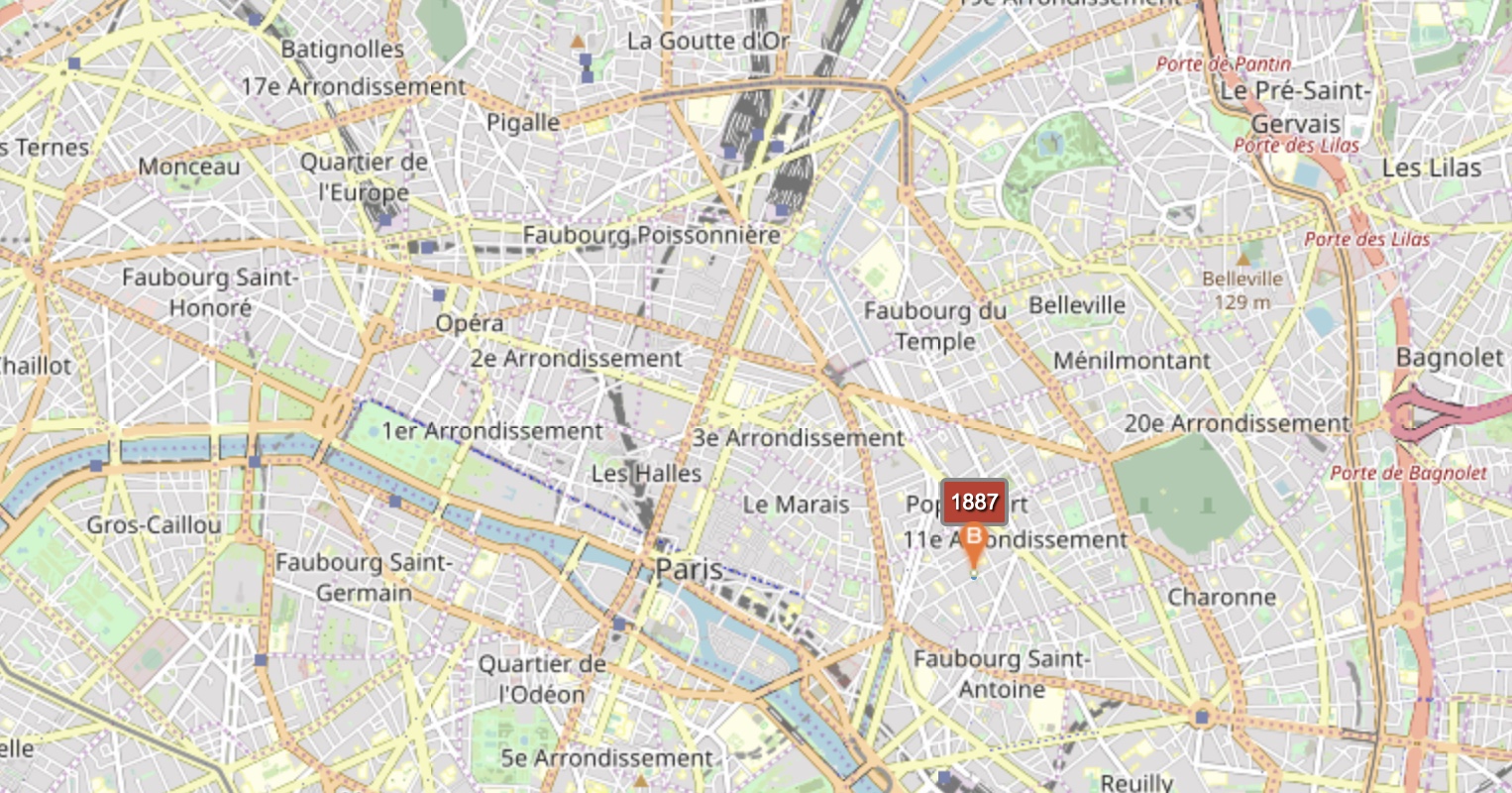

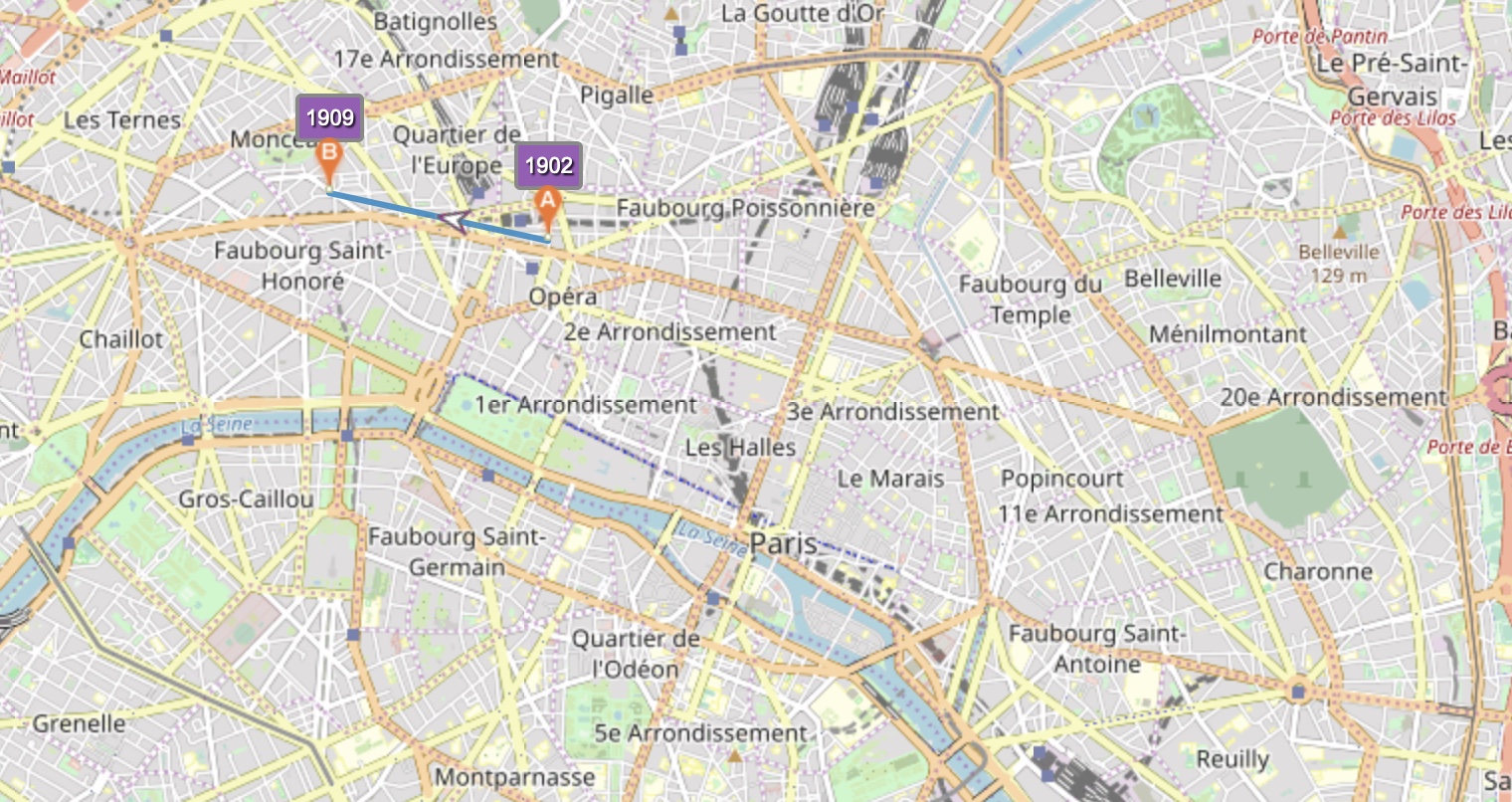

These maps plot the trajectories through Paris of some of Marie Aymard’s descendants who ended up there during the 19th century. The addresses in it are drawn from the traces they left in petitions to the state during their lifetimes, and in arrondissement-level état civil records – of their births, deaths, and marriages, and those of their children. The sample of addresses at which they lived is limited, somewhat randomly, to where they were when they happened to leave a mark in the official record. Still, without claiming to provide a comprehensive picture of the residential histories of these characters, the trajectories are interesting to look at for the similarities and differences between them.

Aside from Marie Louise Allemand Lavigerie, who led a prosperous life and functions as a counterexample to the others (who were either poor or destitute, in their own descriptions), all of Marie Aymard’s descendants who are presented here descended from Jean-Baptiste Ferrand, Marie Aymard’s son and the founder of the largest Parisian branch of the family. Jean-Baptiste had returned to Angoulême from Saint-Domingue in 1795 completely destitute – his shop had burned to the ground in the 1793 Cap Français fire – and upon arrival he was admitted to French emergency relief as unemployable: an almost blind watchmaker. After a brief stint in the Charente departmental administration, he turns up again living in Paris in 1805, with “no property,” “no lucrative employment,” and “living in indigence.”

Jean-Baptiste’s descendants didn’t fare much better than he did – his daughter Françoise Ferrand’s trajectory begins in 1814, the year she was approved for a state pension intended for those who had owned land in Saint-Domingue (possibly via her husband; her father had been turned down for the same pension). The mayor of her arrondissement had certified in 1814 that she was in “distress” and unable to work. Françoise’s own daughter Clara Brébion, born in New York in 1804, and presumably living in Paris with her mother from at least 1814, also left a trail of petitions for relief throughout her life, lamenting her declining eyesight, hard winters, and her troubles with her landlord. (Infinite History, 176, 210.) Clara also appears to have lived with her daughter Rosalie Collet, a seamstress married to a surveyor, for more than a decade. They were last recorded at the same address in 1877, in the 7th arrondissement; by the time Clara died in 1889, they were living apart again, both in the 18th. This is just one case in which evidence of these people’s trajectories, temporally sporadic and often written in bureaucratic boilerplate, gestures by its spare nature at tantalizingly important and compelling questions that it can’t answer. In this case, why did Clara, in her 70s or 80s, move away from Rosalie, on whom she had presumably been relying through preceding years of poor health and worsening economic fortune? Louise Collet, Clara’s other daughter, was a street seller, married to a carpenter.

The purpose of these maps is to illustrate the patterns in the ways these individuals moved through the city over the course of their lives. Jean-Baptiste Ferrand and his descendants usually either moved within a neighborhood or, as their economic circumstances worsened during their lives, followed a generally northwards trajectory away from the relatively prosperous city center and towards the poorer faubourgs to the north. One hypothesis, worth studying, is that they would stay at an address on credit from their landlords, and then move to a new one when that credit ran out and they were evicted.

Among Françoise Ferrand’s descendants, Rosalie Collet stands out as particularly mobile, with 7 or 8 registered Parisian addresses over the course of her life, between her marriage to Raphaël Bossard in 1861 and her death in 1890. Her many recorded addresses are in part an oblique testament to her particular misfortune: she appears in the civil records mostly at the births and deaths of her children, of whom she had 10; only one survived childhood.

Her path – for the most part – follows the typical generally-northwards progression. It’s a ten-minute walk up and around the east side of Montmartre between the addresses recorded at her marriage and at her death, separated by 29 years, and all but one of her addresses are contained in a north-south axis between Pigalle, at the southern base of Montmartre, and the Porte de Clignancourt, just north of it.

But in 1877, Rosalie Collet, whose mother had been living with her for at least the past 11 years, gave birth to a son, Léon Bossard, in an apartment at n. 70 rue de Sèvres on the southeastern edge of the 7th arrondissement, on the other side of the city from Montmartre. Why did the Bossard-Collet family make their jump across the river and back, when most of Rosalie Collet’s Parisian cousins seem to have lived out most of their adult lives within a single neighborhood of Paris, and given that they themselves, before and after that jump, lived exclusively on and around Montmartre? One clue lies in Raphaël Bossard’s profession, as listed in his son’s birth registry: a “mètreur en bâtiment,” or quantity surveyor. The year 1877 marked the last year of construction for the new Bon Marché department store, just a block to the north (the Bon Marché, and its effects on its changing neighborhood and its workers' lives, form the inspiration for Émile Zola’s 1883 novel Au Bonheur des Dames). It’s possible that the family moved in order for Raphaël to be able to work on the department store, but seems unlikely. While the move is visually perplexing when laid out on a map, and its proximity to the Bon Marché and its brevity striking, it seems likelier that a surveyor would have been engaged at the very beginning of a construction project than at the very end.

But in any case, the Bossard-Collet family made their move during a time when the physical fabric of the city was rapidly changing. Starting in the 1850s Napoléon III had undertaken a massive project of urban renewal masterminded by the baron Georges Eugène Haussmann, the prefect of the Seine department, expropriating and destroying huge swaths of the city, and replacing demolished buildings with the now-ubiquitous immeubles haussmanniens with their 2nd-floor balconies and 45-degree slate roofs. Haussmann pierced a network of wide boulevards through crowded neighborhoods (of which one, now the Boulevard Raspail, led straight up to the intersection where the Bon Marché would be built), and created public squares and parks. The second empire would have been a time of ample work for a Parisian surveyor like Raphaël, or a carpenter, like Louise Collet’s husband.

While Jean-Baptiste Ferrand’s descendants lived mostly in the interstices between the new and emerging boulevards and moved obliquely to the Haussmanized neighborhoods, only very briefly dipping into one in the case of the Bossard-Collets, Marie Louise Allemand Lavigerie functions as a counterexample to the prevailing northwards pattern. A third cousin of the others in these maps, she came from one of the wealthiest and most politically and culturally successful branches of Marie Aymard’s family. At the time of her wedding in Angoulême in 1851, she declared her personal property to be valued at 6,000 francs and received a 30,000-franc dowry from her parents. Her uncle, Scipion Allemand Lavigerie (whose heir was her father), had grown wealthy as the founder of a provincial bank in Le Mans. During the 1850s and 1860s, when Marie Louise’s husband Henri Portet was a partner there, the bank became even more successful, profiting from arbitrage in the London markets and investments in French marble quarries, the Galveston-Houston rail line, and the Panama Canal. (Infinite History, 253.)

The part of Marie Louise’s life depicted in this map begins more than a quarter century after that wedding. The family left Le Mans for Paris, after a messy and litigious dissolution of the Portet-Lavigerie bank, and after Henri Portet was determined in a legal proceeding to have committed “serious faults” in respect of “fraudulent and lying accounts.” They were still wealthy – in addition to their Parisian addresses, they owned a villa in the fashionable Bordeaux-adjacent station balnéaire of Arcachon. Marie Louise’s trajectory, graphically different from the others on the map, was also economically different. Between the death of her husband in 1902 and her death in 1909, she is recorded at two addresses along an East-West axis, both in the prosperous – and recently Haussmann-renovated – center of the city.

These maps are fluid and ephemeral, recorded only in patches, showing the movement of people over the courses of their lives, the trajectories in them subject as much to the health, temperament, and fluctuating fortunes of their characters as to the urban economy of the second empire. The map of the changing cityscape of Paris in those years is of a different nature – planned, official, fully documented, built in stone. One part of this project is an exploration of the knowledge, missing from the second kind of map, that the first kind can bring. During the Haussmannian years of radical urban change depicted here, it is particularly interesting to juxtapose the two maps, one of buildings, the other of lives. Some of Marie Aymard’s Parisian descendants, like the Collets, seem to pass through the holes in the net of Haussmann’s grands boulevards and renovated neighborhoods. Their near invisibility in the new landscape may nevertheless, as in the case of the Bossard-Collet family, hide their involvement in building it. Marie Louise Allemand Lavigerie and her family were by contrast deliberate and visible participants, geographic and social, in the movement of Second Empire Paris. Marie Louise arrived from the province with new banking money to live at two addresses in the prosperous and Haussmanized center of the city (near, in fact, the Boulevard Haussmann) – a large-scale economic and geographic upwardly mobile trajectory through France that closely follows the one Zola described three decades earlier in La Curée. In 1876, Marie Louise’s daughter Valentine married Olivier Boittelle, the son of the prefect of the Paris police and a cousin of Georges Eugène Haussmann. And so it was that the Baron Haussmann acted as the groom’s witness at Valentine and Olivier’s wedding.